Over the years, so many of us have worked in environments where the stress gets so intense that you half-jokingly fantasize about throwing something at your manager. Instead of doing that in real life (please don’t), I made a game to help all of us release that energy: Hit Your Manager.

https://www.hitmymanager.com/

The story starts with a sad, overworked employee being bullied by a terrible boss. But one day… he finally decides he’s done. This little worker is ready to stand up for himself.

This is the first time I fully poured my heart into making a game, and wow — it took me hella time. Here are some things I learned along the way, especially about using AI to design.

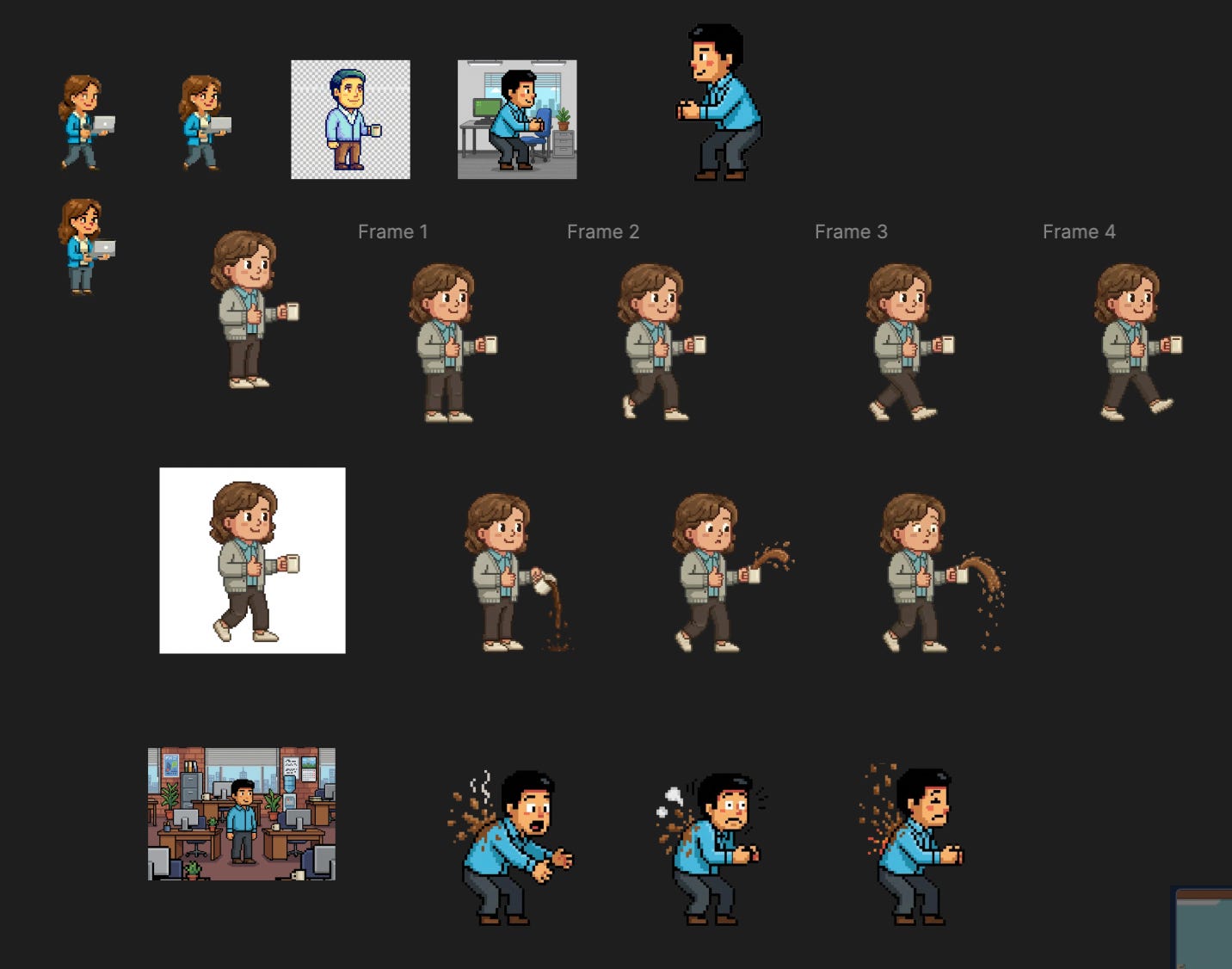

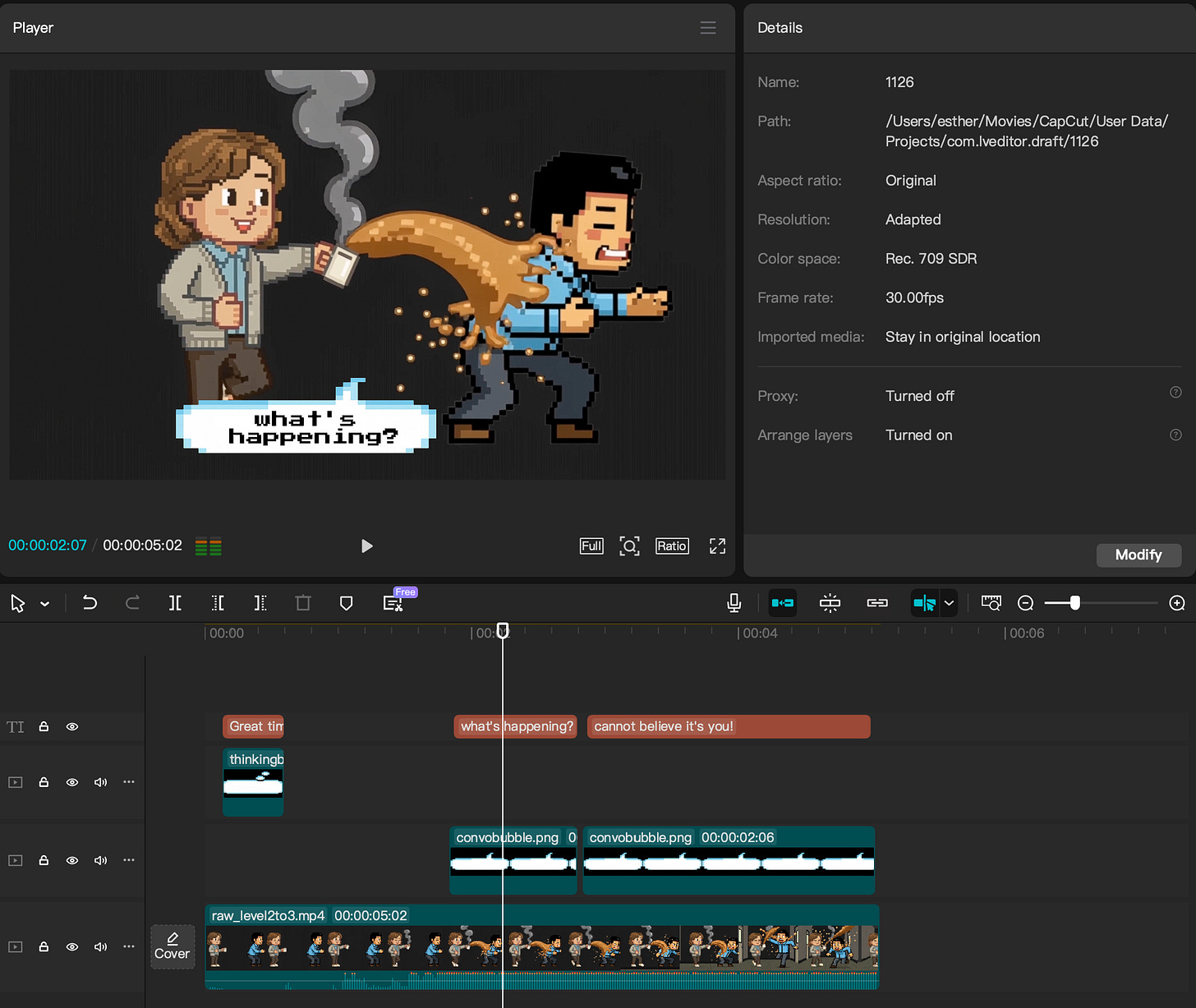

1. AI can create something impressive fast — but consistency is a beast

AI is great at generating those eye-catching first drafts. But getting consistent characters, consistent styles, consistent sprites? Not easy. Not even close.

It kept giving me designs that didn’t match the theme, or characters that mutated every few frames. I spent so much time fixing weird eyes, weird faces, and weird randomness.

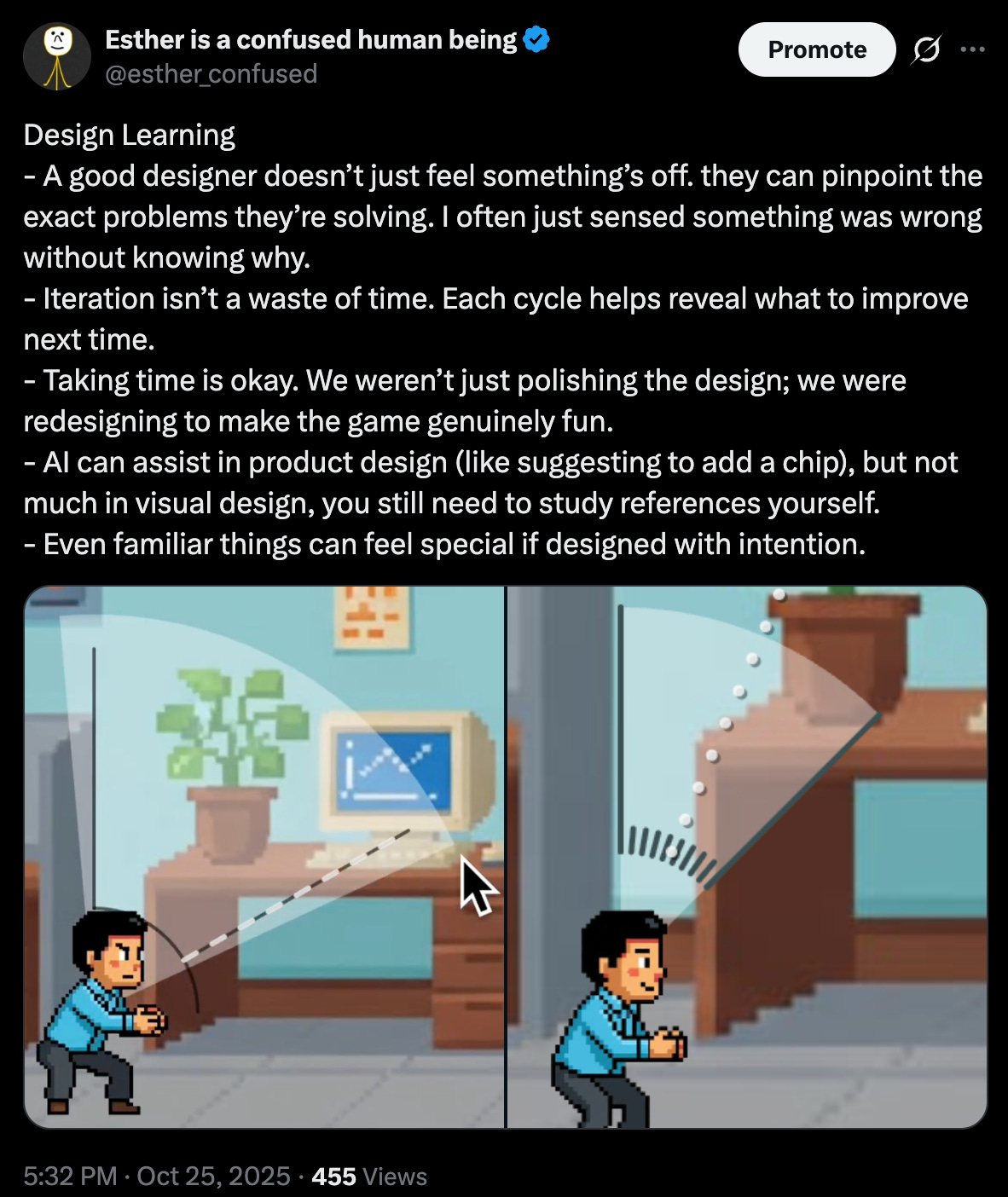

2. Prompting is a real skill (and I don’t speak “designer”)

My designer friends know all the magic words, “chip,” “composition,” and a bunch of terms I’ve never used in my life. They speak the language that helps AI stay consistent and intentional with its design.

I… absolutely do not.

So when I prompt, AI just freestyles. And the freestyle is almost never what I want. Learning to talk to AI like a designer is basically learning a whole new dialect.

What’s funny is: in programming, it’s the opposite. I can fix a bug instantly by talking to AI in engineering language, while my designer friends get stuck because they don’t know how to “speak code” to AI. It made me realize prompting isn’t universal, it’s domain-specific.

3. Simple ideas are not simple when you try to make them good

“Just make a game where you hit a manager.” Sounds easy!

But it’s quite the opposite.

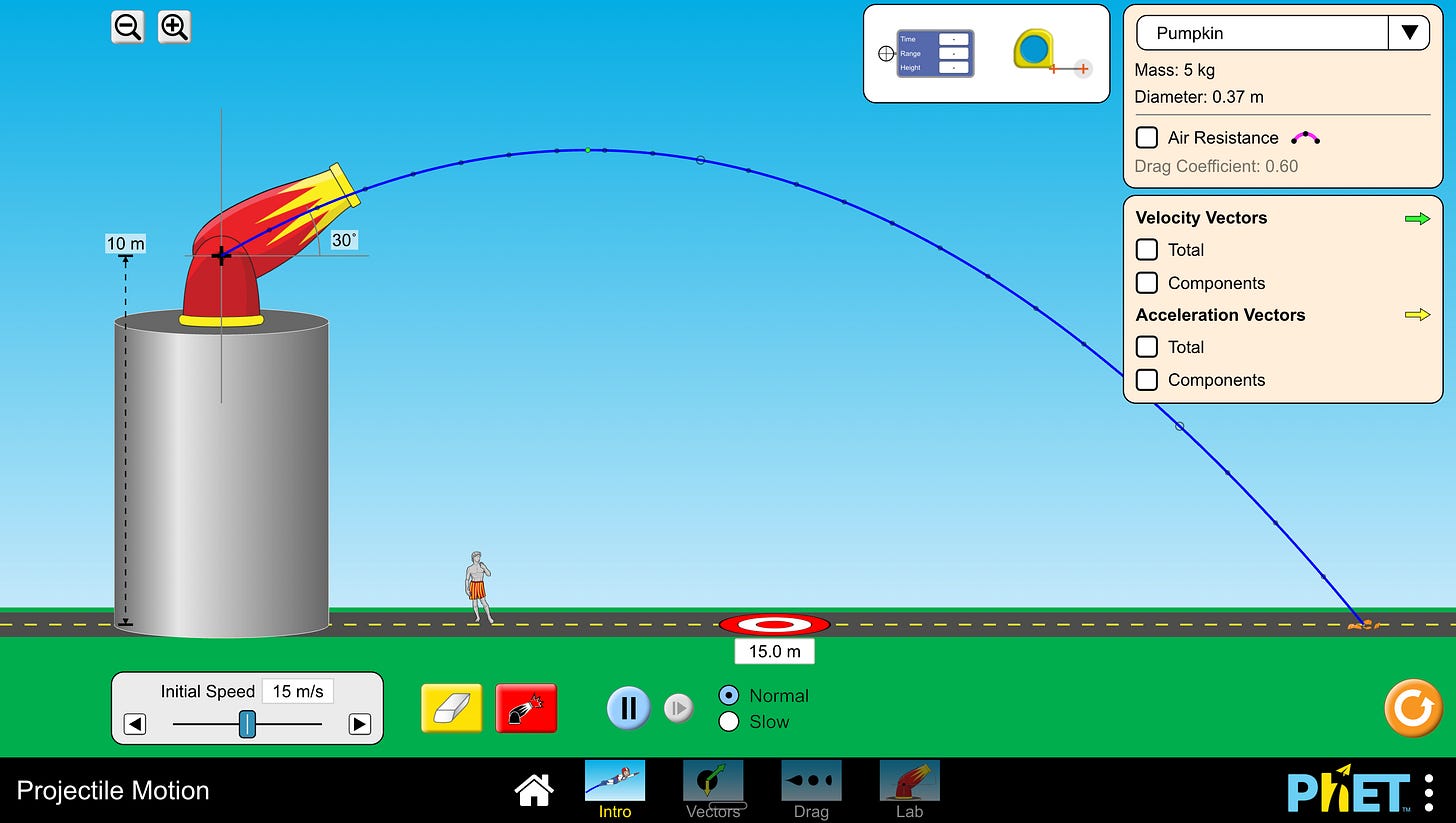

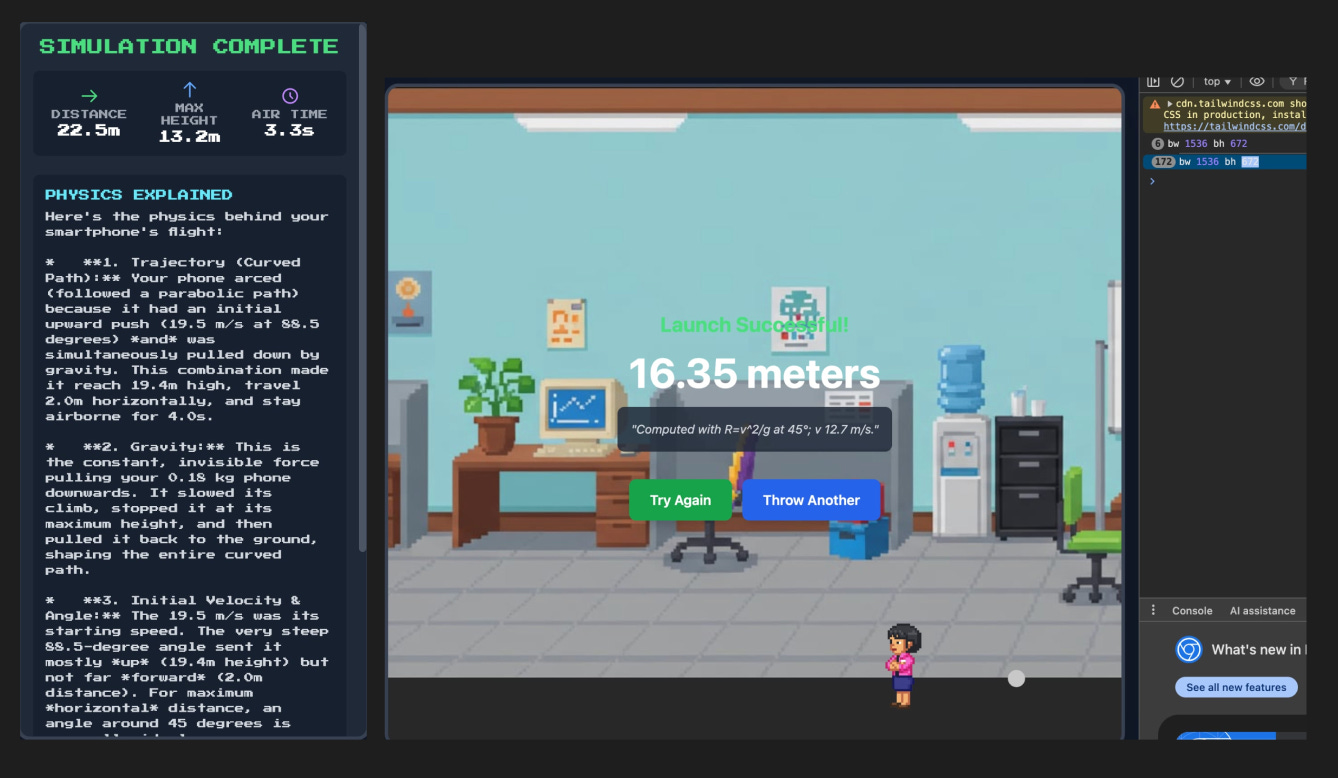

Initially, we made the game because we want improve this current physic engine about gravity.

We originally wanted people to scan real objects and learn physics by playing with them. It sounded exciting — scan a cup, toss it in the game, and watch real-world physics come to life.

But it’s actually very hard to do it well. Building accurate physics engines takes a long time, and once we finally got gravity “right,” the gameplay wasn’t fun. Objects stayed in the air for so long that everything felt slow and boring. Real physics ≠ good game design.

So we pivoted toward a storyline everyone can instantly resonate with: hitting someone. Simple, emotional, universally understood.

But to actually make this idea work, we had to

build a clear storyline

test the mechanics with real users (some found it too easy, others too hard, so I spent forever tuning tiny details),

iterate until the gameplay made intuitive sense

And that’s just the creative side. There’s also all the invisible work behind the scenes:Most players are on mobile → so now I have to redesign the entire experience for mobile. API costs are too high → so I need to rethink the architecture and optimize everything.

A “simple idea” becomes complex the moment you try to make it good.

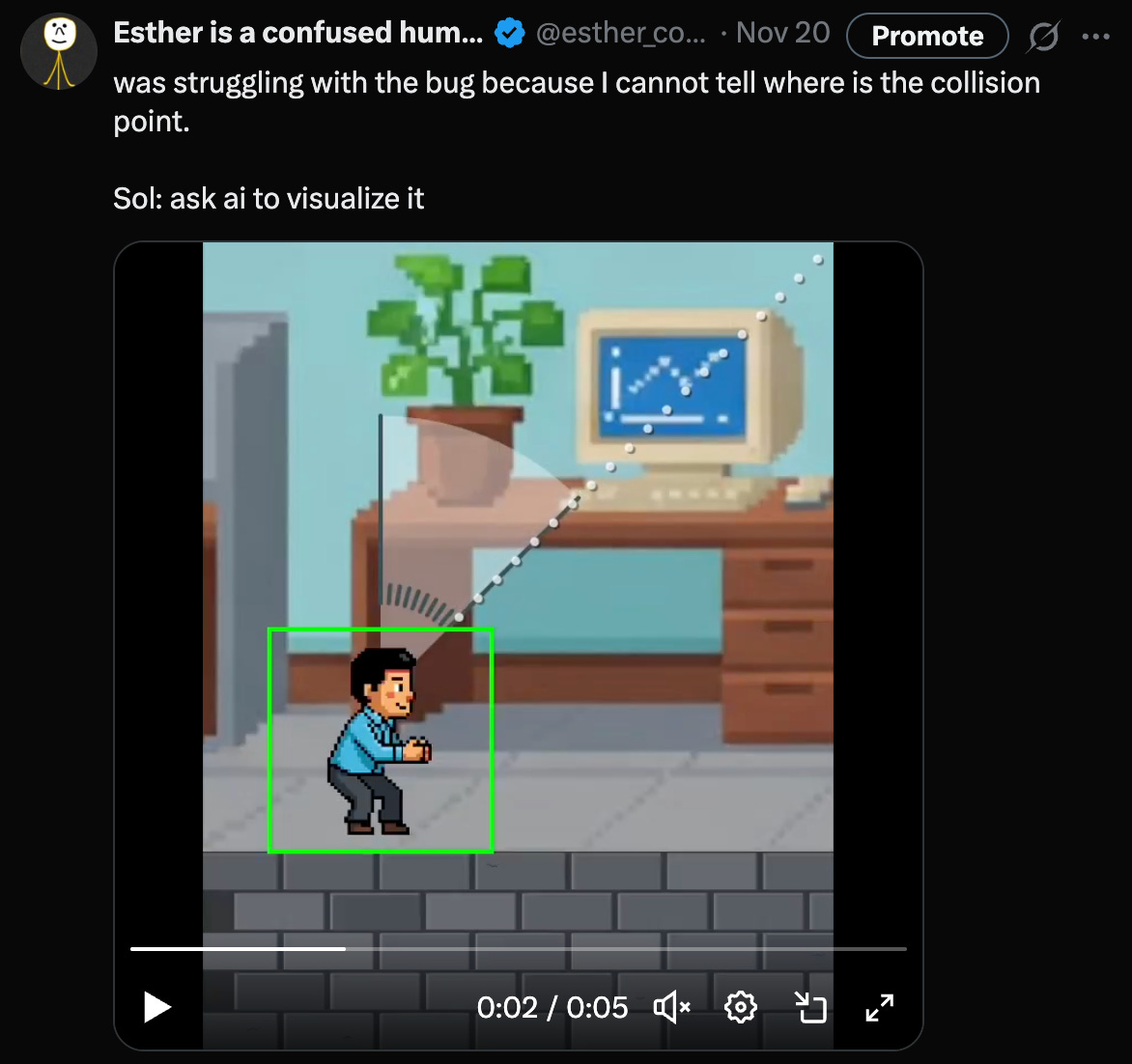

4. AI shines when you use it as a debugging with imaginations

One big problem I had was detecting collision using x/y positions. I was confused for hours. Then I asked AI to visualize the collision area with a green box. Instantly the issue became obvious. Sometimes, AI isn’t a good designer, but it’s an amazing assistant when you need clarity.

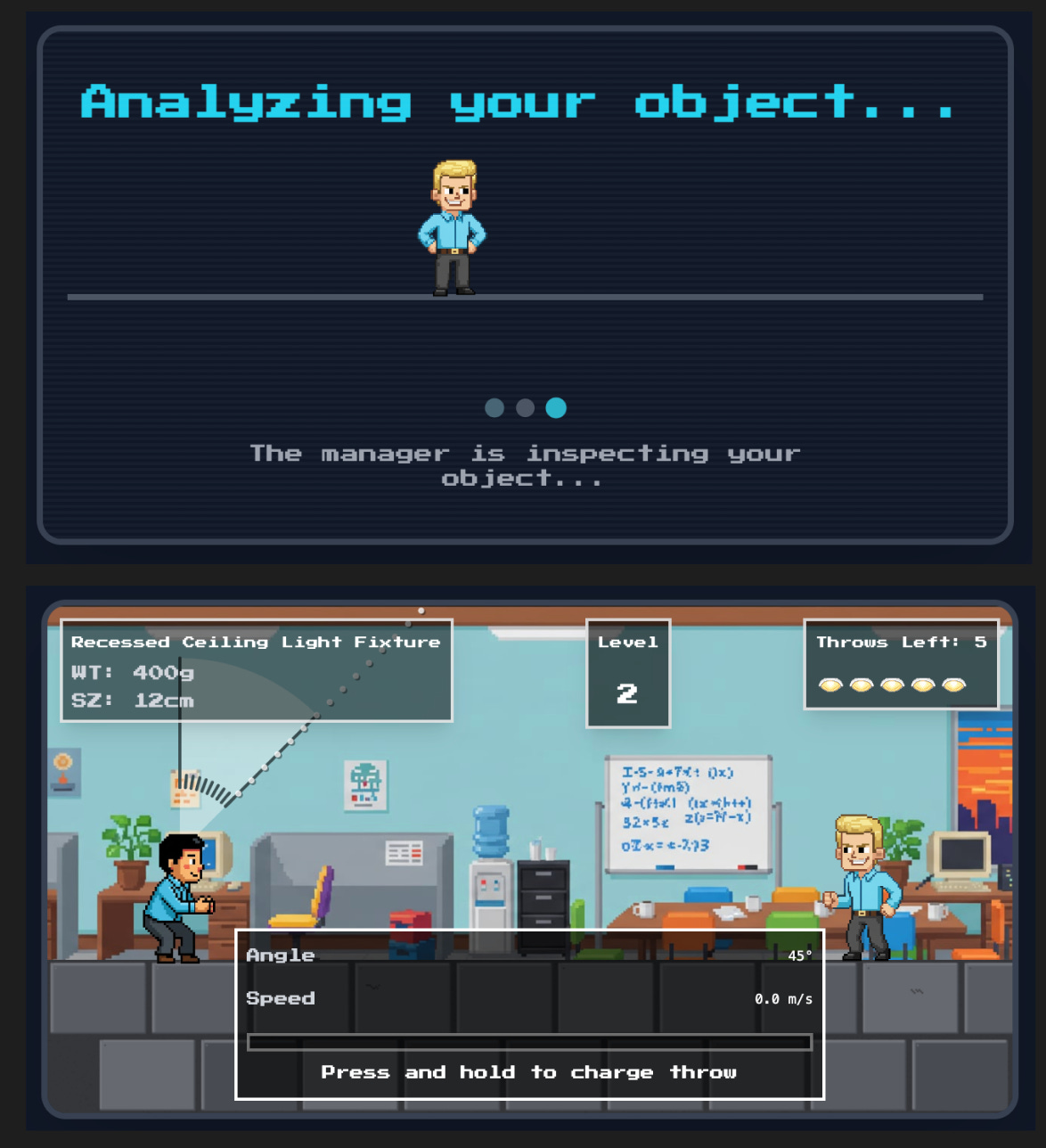

5. Storytelling still matters in game design

Good gameplay needs to feel connected to the narrative. Even a simple arcade game needs progression that makes sense.

For example:

Level 1: the manager is just standing

Level 2: the manager starts walking around

The story advances, and the difficulty increases naturally. Designing these transitions required more creativity than I expected.

6. Boring ideas aren’t always boring

We originally planned to make a very basic throwing game. In the first hour of the hackathon, we were already bored of it. But my designer friend refused to give up. We kept pushing, refining, adjusting, and the game slowly transformed into what it is today.

That process taught me how to collaborate with both AI and human designers. People love to say you can just “vibe code” your way through things, but as a programmer I learned the opposite: polishing a game takes way more time, thought, and obsessiveness than I ever imagined.

I started this project because I interviewed with Brilliant and learned interactive programming with p5.js for the interview challenge. I didn’t get the job, but that interview somehow grew into something much bigger.

Now I’m excited to take these lessons into future projects, maybe even building more interactive learning experiences like the ones Brilliant creates.

Who knows? This might just be the start of something cool.

love this process!