I would like to share some insights on building fast and breaking fast, which I learned after spending two weeks building with my flatmates. There are three main principles: one for building quickly, one for breaking down fast, and one for integrating these two processes seamlessly.

Principle 1: Can we complete the MVP in two days?

Here, we define MVP (Minimal Viable Prototype) as something that is completed but barely works. This idea is based on Linus’s article “How I side project,” in which he claims to spend only 6–8 hours prototyping an idea before deciding whether or not to pursue it. After one MVP trial, our group decided to set the MVP period at two days.

I understand that two days might seem like an impossible timeframe, but trust me, it’s doable. Instead of attempting an ambitious but bloated project, try to focus on something feasible within that timeframe. There are two advantages to adopting this mindset. (1) It provides momentum to build. You won’t slack off or shy away from difficulty. (2) It forces you to focus, putting you in the MVP hat. You won’t wander aimlessly through research and ideas, because you’ll want to quickly test if it works. This MVP hat will grant you speed, motivation, and focus on the right problem when you start building.

Let me describe what I mean by the MVP mindset. For instance, a flatmate once asked me how she could learn data analysis for her startup. This was a big ask, as data analysis takes many people years to master. Instead of asking her to learn the entire field of data science, I advised her to clarify what she wanted to achieve with the analysis.

If she wanted to learn about her students’ engagement from Discord, I suggested she use Discord’s analysis tools. If she wanted to see the performance of her newsletter, I recommended existing analytics tools or a Chrome extension. Rather than scraping and analyzing the data herself, I suggested she focus on understanding some basic but crucial metrics for engagement and performance. Even using Google Sheets to analyze would be better than learning data analysis in R and Python. Since she didn’t need fancy visualizations for others, she just needed to see the performance for herself. Understanding important metrics is her MVP, not learning data analysis. I think now you can easily see the difference between a school mindset and an MVP mindset. The MVP hat emphasizes learning while doing, rather than learning before doing. We build fast.

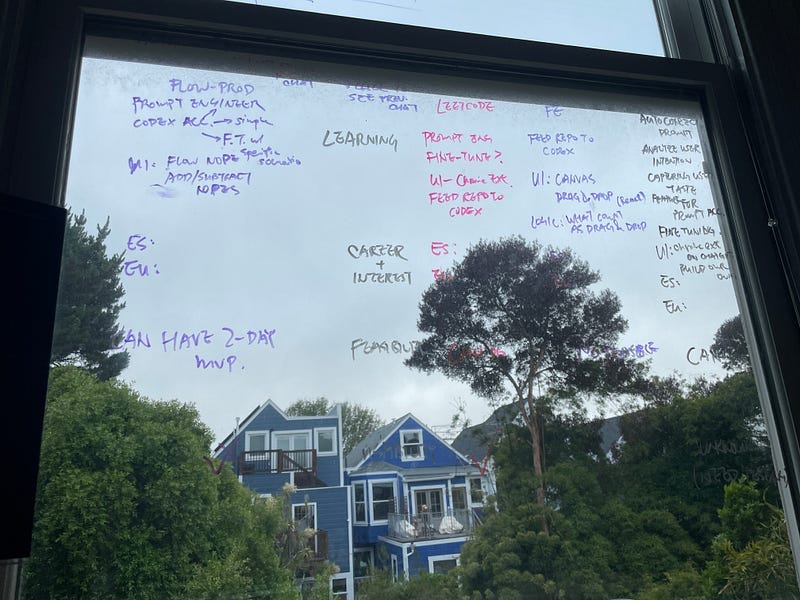

Principle 2: Evaluate your project based on its tech stack, feasibility, usability, and interests

This principle is about how to choose the right project from among many ideas that pop up in your mind. To decide which project to pursue, we use the following four dimensions: tech stack, feasibility, usability, and learning & interests.

Tech stack: What technologies and tools will we need to use to complete this project? We will lay out the entire project map, breaking down all the pieces we need, including tools, and the specific process to complete this project.

Feasibility: Which project is the most feasible given the existing tools, technologies, and skillsets in our two-day MVP? What is the potential breaking point? We lay out potential roadblocks that we might encounter in the process.

Usability: Which project will be useful for at least one person on this planet?

Learning & Interest: Which project can accommodate both teammates’ personal and professional interests and our learning goals?

This is a powerful framework because, instead of taking on too many projects and ideas at once, these four dimensions lead us to converge on practical, feasible, and personally interesting projects.

For instance, our idea of converting flow charts into code through AI isn’t feasible because we realize we have too many bugs in the code.

During discussions, we will identify potential breaking points and ask, “If this doesn’t work, what else can we do?” Additionally, I will ask, “Is there a simpler way to achieve this part?” The true value of this principle lies not only in selecting a solution together but also in scoping the right MVP before diving too deep.

For example, we consider an AI code-fixing idea this week. It may sound interesting and feasible at first, but after testing it with our code in the afternoon, we encounter a major problem. AI cannot understand the relationship between different code blocks, so while it may fix one block of code, it could create more issues for other blocks. Through this quick failure, we learn that this project is much less feasible than we initially thought. We save time by not building the entire pipeline and identifying this bottleneck early on. We break things fast.

Principle 3: Stop building and reflect

After two days of working on the MVP. regardless of whether we finished it or not, we stop and reflect on what we’ve learned. The purpose of this reflection is to avoid getting bogged down in the problems of both the work and the collaboration, and instead use what we’ve learned to improve for the next iterations.

We schedule a meeting to discuss the following questions:

What went well in this project?

What went wrong in this project? How can we improve for the next time?

What went well in this collaboration?

What went wrong in this collaboration? How can we collaborate better in the next round?

For example, in this round, we wanted to create auto-prompting suggestions for ChatGPT. However, we only completed scraping the data and realized that latency was a major issue. Instead of continuing to try to solve the problem, we stopped and my flatmate asked,

“Let’s think about it independently. If it’s not possible anymore, can we pivot and use the scraped data to do something else?”

Even if this round is ultimately a failure, we have gained knowledge and data that we can use for the next round.

Collaboration is also important. I told my flatmate that I didn’t appreciate him taking away my personal time for his work and that his communication style doesn’t work for me. After talking it out, we were able to collaborate better in this round. For instance, when we got stuck on a problem that was in the other’s area of expertise, we switched chairs and resolved the issue immediately. This idea would not have been possible if we weren’t comfortable with each other. Overall, this principle supports the speed of work and collaboration, allowing for mistakes and providing clear next steps and learning objectives.

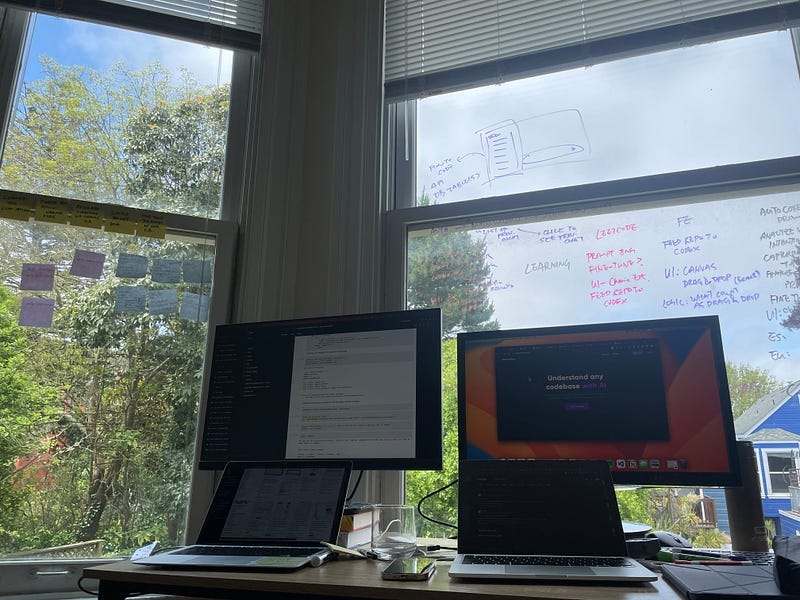

Now, our house looks like a messy, chaotic hacker house. However, I have exercised my “0 to 1” muscle and feel much more confident about starting from nothing.

This is the 25th post from my 30-day writing challenges. I was inspired by Tung Nguyen, a friend who is a famous blogger. He overcame the fear of creation through mass-producing blogs and eventually found his own niche audiences.