What I learned about money as a young adult

free your energy, not just save money

When I graduated and stepped into adulthood, I assumed my biggest financial lessons would come from spreadsheets, budgets, and salary numbers. Instead, almost everything I learned came from psychology: fear, confidence, mindset, and the way I related to uncertainty. The most expensive decisions I made were not financial mistakes, they were energy mistakes.

The people who are successful don’t obsess over small savings

One of the first patterns I noticed among people my age who were doing exceptionally well is that they rarely agonized over tiny expenses. They didn’t spend hours comparing prices or hesitating over minor financial decisions. They made quick choices, accepted the cost, and redirected their attention to the work that actually created value.

But when you’re young, your sense of what counts as “a lot of money” is shaped by limited experience and limited confidence. A $100 difference in flight feels enormous. I overthought on whether I should pay $200 extra rent for a better house. And when your days are full of stress about housing, visas, or career stability, it becomes nearly impossible to focus on the work that could actually move your life forward.

Living from fear is expensive, even when you think you’re being careful for the worst case scenario

After graduation, I made almost every decision from fear. I didn’t believe I could find a stable job or stay in the country long-term, so I avoided long leases and kept choosing two-month or three-month stays “just in case.”

In the two years after college, I moved four times in San Francisco. Ironically, short-term leases were more expensive, but I still chose them because fear convinced me that paying more in the short run was safer.

Looking back, preventing disaster wasn’t inherently wrong. But spending all my energy avoiding the worst-case scenario meant I had none left to rise toward the best ones. The time I spent searching for the next temporary place or coordinating furniture was time I could have invested in actual growth.

I treated the worst-case scenario as catastrophic, even when the chance was low and the cost was manageable from my point of view today.

Shifting from a saving mindset to an investment mindset

A founder friend once told me he now sees spending on having fun as an investment rather than a cost. And slowly, I realized this is how most of the successful young people around me behave.

For example: Whenever I moved, I spent days hunting for cheap furniture and asking friends to help me assemble things late into the night. Meanwhile, the people I looked up to simply ordered everything at once, hired someone to assemble it, and went back to work.

What felt “too expensive” to me allowed them to finish in a week and stay energized.

What felt “frugal” to me left me exhausted for an entire month.

Decisiveness is a financial skill

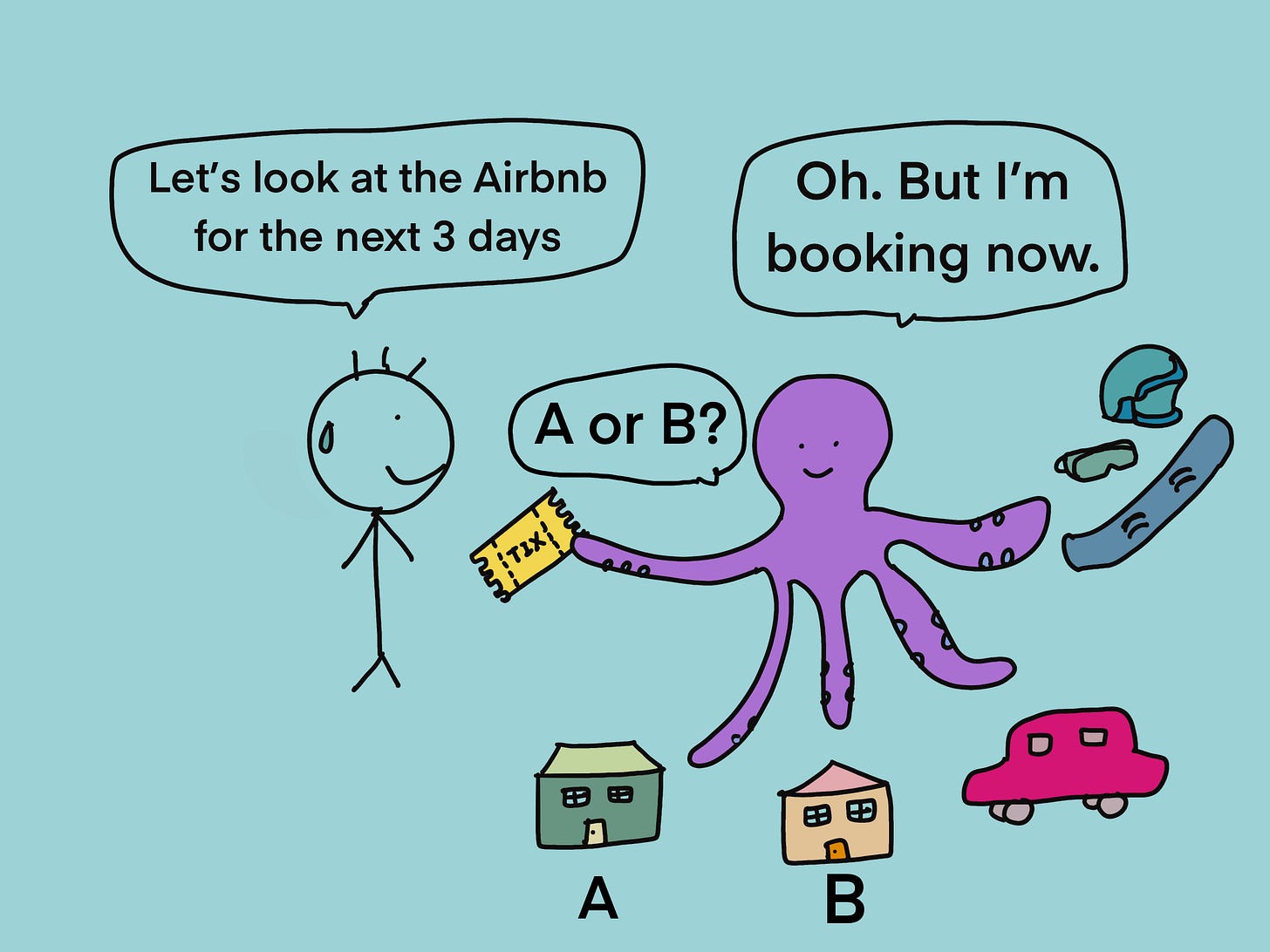

Indecision is extremely costly.

I used to spend days checking flights, waiting for prices to drop, agonizing over refundable options. I told myself I was being smart. But most of the time, the price just went up—and meanwhile, I carried the mental load of thinking about it every day.

When a friend helped me plan a snowboarding trip, I watched her book the resort, car, and housing in thirty minutes. I was shocked at how fast it happened, and how light I felt once the decisions were off my mind.

I realized the money saved through endless optimization was rarely worth the stress it cost me.

You cannot beat the market through wishful thinking

Over the years of renting in expensive cities, I learned a painful truth: If many agents tell you the market rate for a certain neighborhood, that is the market rate. Hoping to be the exception usually leads to wasted time, stress, and, often, worse outcomes.

A few times, friends and I refused to take the normal price and searched endlessly for a “better deal.” We ended up stressed, behind on time, and once even in an illegal apartment.

Good deals exist. But “too good to be true” usually is problematic. Once you’ve done 90% of the research, the final 10% rarely justifies the emotional cost of squeezing out tiny optimizations.

It’s okay to make small financial mistakes

Almost all my hesitation came from the same root: fear of choosing wrong.

My dad once told me,

“It’s okay to make mistakes. There’s always risk in any investment.”

I’m currently searching for housing in New York, and I’ve been afraid that if my job doesn’t work out, I’ll be stuck with a long lease and debt. But my dad reminded me:

“You won’t lose everything. Worst case, you sublet cheaply and lose a little money. That’s life. No one predicts everything perfectly.”

Suddenly everything softened. Why was I treating every decision like it would ruin me? Why was I unwilling to tolerate even small, recoverable losses?

Permitting myself to make mistakes felt like permission to breathe.

The real lesson: direct your energy toward the life you want

My biggest financial education wasn’t about budgeting or investing, it was about an ability for good decision making. The real cost of my early decisions wasn’t the money I spent, but the focus I lost.

Here’s what I now tried to practice:

Make more small bets.

Make faster decisions.

Don’t pour energy into optimizing tiny costs.

Don’t assume you’ll beat the market.

Allow yourself to make imperfect choices.

Put your time where the long-term rewards are.

Invest in the life you want, not just the life you fear losing.

The goal isn’t to be perfect with money. The goal is to free up your attention so you can do the work that actually builds your future.

These are the lessons I’ve learned as a young adult.