The perspective of organizational capacities

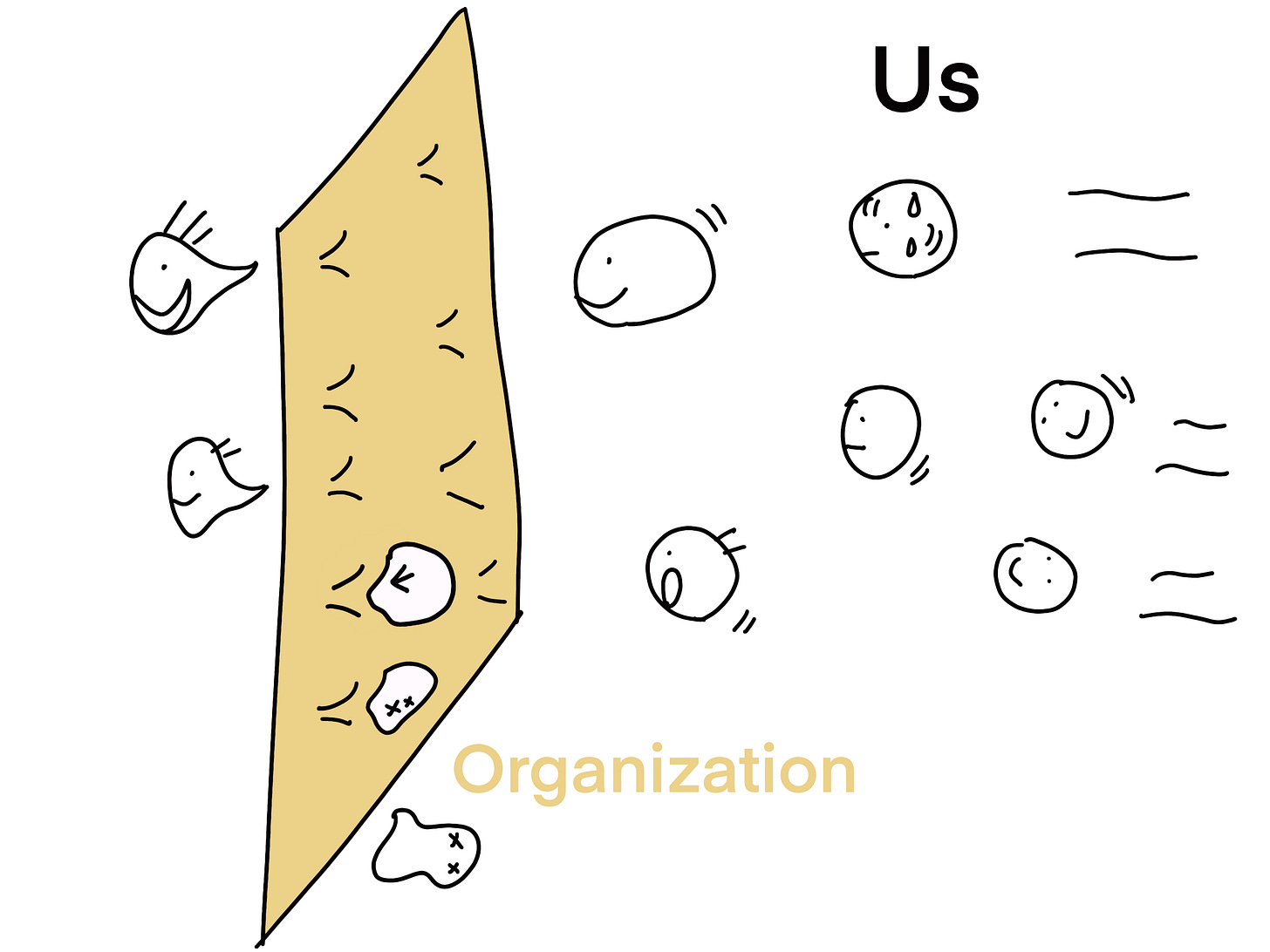

When we talk about capacities, we usually think of individual capacities. If an employee can finish their work on time and deliver what the company needs. However, little do we know that the capacities of an organization will potentially limit or unlock the individual capacities too. For instance, an organization that has significant overhead will only value a very high-profit margin product, such as 40%. In a way, it means that all the product ideas that will yield less than 40% of the predicted profit margin will be discarded. The company is incapable of targeting low-margin markets. And this applies to people too.1

So what do I mean by organizational capacities? I will use the definition from the innovator’s dilemma: resources, processes, and value. Resources are the assets of an organization, such as technology, people, and physical assets. The process is the pattern of interaction, coordination, communication, and decision-making that can range from manufacturing, product development, procurement, budgeting, planning, and so on. Values are the perceived benefits of a product or service.

Take process, for example. A process can define capacities in executing certain tasks while defining disabilities in executing other tasks. The established process will define the capacities of an organization.

For instance, market research and planning as a process is good for new product language in existing markets but useless for emerging and poorly defined markets. On the other hand, if you don’t do any research but experimentally and intuitively deploy products in a well-defined existing market. It will probably soon be a suicide. A small organization usually has a better process (e.g. no need to do data analysis and PowerPoint) to explore emerging markets. That’s why they have a better capacity to innovate.

The process also limits or unlocks individual capacities. Let me use myself as another easy example. When I worked at Meta, we had abundant resources—money, research, people. Therefore, I had a lot of freedom to explore with the resources. The deadlines were looser, but it required better coordination across teams to make small and careful changes. Most of the time was spent streamlining the processes, ensuring that people collaborated well. So I spent a lot of time writing documentation that people could quickly understand and appreciate. Big companies spend most of their energy managing people's processes of coordination.

On the other hand, when I worked at a <10 people startup, we had few resources. Everything needed to be fast, fast, and fast. They allowed me to have a lot of decision-making power and responsibility. Yet, there was no space to explore as everything was very pressing. The process of decision-making was not on the organization but on individuals’ initiatives.

Processes and values determine what an individual can do and what decisions they will make in their work, and most people call it culture. That’s why people say that the founder and the first 10 employees build the culture of a company. In early-stage startups, founders are the main decision-makers so the employees end up copying their founders’ processes and values.

Therefore, when people are talking about "a right fit" for picking the next company they want e.g. a good team, and impact to make… they are essentially discussing a match between their development criteria and the capacities of the organization.

How to find a good manager?

So, how can I find a good manager?

Thinking from this perspective, it is, in fact, saying that a good manager in big tech can hardly be as good as they used to be if they join a startup, because startups have strong survival pressure. I know this is a bold claim, but I hypothesize it’s generally applicable. It doesn’t mean that a medium or big size company will definitely give me a good manager, but it allows and encourages better managers to exist.2

In fact, asking if I will have a good manager is not enough. I ask “Does the organization have the processes and values for me to succeed?” A good manager will not survive long in an organization with a terrible culture while a good culture will cultivate good managers.

Let’s also break down what "finding a good manager" means. If I closely think about this need, it’s not exactly about the need to be led. It’s the need to learn best practices from programming to collaborating in my early career. I can learn coding through YouTube and collaborate on side projects, so the point of working is learning the things that I cannot learn with my current resources. For me, it means establishing best practices that I cannot easily obtain without enough experience and scale. For instance, the technical side is the use of tools and processes for scalable products; the people side is the way to mature my leadership, my emotions, and my decision-making while learning to advocate, persuade, and negotiate with others.

Always an action plan for Esther in the end, of course. Since the job market isn’t great, choices can be limited at this moment. I decide to put most of my resources into a medium-sized startup from searching to interviewing. (If you know the US a little bit, you will know the action plan to find a small startup vs medium-size company vs big tech is three different games.) A 3-year work visa in the US isn’t long. While gaining any experience is useful, how I want to spend my time for the next two years might be the most important question for me at this moment.

Thoughts on ownership: The idea of organizational capacities extends to ownership too. When people talk about ownership, the management usually assumes that the individuals have the “free will” to exercise whatever they want to do and hence should be held responsible for whatever they are doing. In reality, people are constrained by the organizational capacities. For example, I have ownership to brainstorm how to work on my project in Meta, but my manager’s approval is a must before starting it. vs. I build whatever feature I want for the startup but the success of deploying and maintaining depends on my founder.

A counterexample is Uber. My friend who works at Uber experienced big changes from the manager because of the organization. Her manager was initially nice and chill, but all of a sudden became very picky, grumpy, and problematic as the management realized the team might be laid off if they could not compete with Indian teams. I find it a good example to say that people aren’t what they are capable of. They are inherently shaped by the resources, processes, and values in an organization.